Table of Contents

What Are Urinary or Kidney Stones & Why & How Are They Formed?

Kidney stones are a common problem, so knowing a bit about them is ideal.

There are different types of stones. The most common stones are made of calcium oxalate, then calcium phosphate, then uric acid, and a minority of cases are due to cysteine, struvite (also called magnesium ammonium phosphate – which is associated with chronic urinary infections) and other rarer components.

Medical conditions like diabetes, metabolic syndrome, excess of weight, gout, primary hyperparathyroidism, some cystic diseases of the kidneys and rarer conditions of the kidneys have been associated with urinary stone formation; even gastric bypass surgery. In addition, certain dietary or lifestyle habits like drinking not enough water and taking certain supplements like vitamin C or calcium in excess, and some medications, can also predispose to urinary stone formation.

All these situations favour that patients pass more calcium, oxalate or uric acid in the urine (or the other lesser crystals); which then deposit in the urinary system. Or these situations can lead to lower levels of citrate in the urine, which in a normal level is protective, or can modify the acidity/alkalinity of the urine, facilitating the deposition of many of the salts I mentioned.

A lower urine volume caused by not drinking enough water is also an important predisposing factor as the urine is more concentrated or what we called ‘supersaturated’ with many of the salts that lead to stone formation. This is one of the reasons why we should be drinking sufficient amounts of water daily (but not in excess either).

Symptoms & complications from urinary stones

Some people might actually notice the passing of some small stones or gravel through the urine, even without symptoms.

Larger stones can be really painful if passed, or because they have caused a certain degree of obstruction in the urinary tract.

If they were to obstruct totally the passage of urine, they can cause acute kidney failure, making the patient feel very ill, or they can cause permanent damage to the kidneys with chronic or even total kidney failure. For these reasons, it is pivotal not to leave this unattended.

The size of the stones is the main factor that determines if the stone will be passed in the urine or retained. Typically the size limit is around half a centimetre (or less) for the stone to be passed. And there are many people who have passed stones without noticing.

On the other hand, stones of around 1 cm or more are unlikely to be passed spontaneously; whilst stones of mid-range size (between half a centimetre and a centimetre), tend to be a ‘painful gamble’ – they might be passed or not; but if so, it can be very painful. In this scenario, in some cases, medications like tamsulosin can be given to promote passage of intermediate size stones if they are located in a position that can facilitate the flow of the stone.

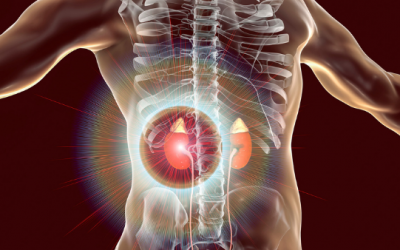

The pain of urine stones is quite characteristic starting on the flanks and going down to the genitals (sort of following the urinary tract system) and it is called renal colic. It is severe and some patients can feel ill with nausea and vomiting.

Urinary stones can also cause injury to the urinary tract and patients can have burning sensation while passing urine or wanting to go frequently to the toilet; or they can notice blood in the urine; which can be scary and prompts patients to seek medical attention.

Fever can occur and typically indicates that the stone has caused complications with an infection; which must be treated.

How urinary stones are treated?

As mentioned before, there are few types of stones with different associating causes; and some distinct treatment or preventive measures must be implemented, so, our diagnostic strategy and treatment advice must be personalised.

When the stones are of significant size, or they produce symptoms, or they are complicated eg with an infection, obstruction or different degrees of kidney failure; it is ideal that patients are co-managed by urologists, as they are the surgeons who eventually can remove the stone or relieve a urinary tract obstruction, if necessary – to prevent or minimise damage to the kidneys.

There are different methods for stone removal depending on stone location, urgency, accompanying complications and co-morbidities of the patient.

If the urinary stone is obstructing and complicated with infection or kidney failure, the urinary system can be decompressed using a nephrostomy plus urinary stent insertion; which means putting a tube piercing the skin near the kidney going all the way to the main urinary tube; so to drain the stagnant urine, and many times another tube or catheter needs to be left inside the urinary tract for different periods of time to maintain the urinary tract opened. As mentioned, this is part of the expertise of the urologists more than the nephrologists; and they can advise patients better on the suitability of this and the treatments I will mention next.

If there is no emergency, typically urologists suggest either removal of the urinary stone by ureteroscopy, which means introducing a camera tube from the urethra all the way to the ureter where the stone might be, with the aim to remove it. Also, extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) or laser lithotripsy can be used. Simplistically speaking, they work by shattering the stones into smaller pieces that can be easily removed or passed in the urine. It seems to be that ureteroscopy is more effective but is invasive. However, some stones need to be removed through surgery, e.g. laparoscopically, especially if they are too big or complicated or if the previous procedures fail.

If the urinary stone is complicated with a urine infection; a urine culture must be obtained and patients should be started on antibiotics, and the type of antibiotics modified once the bacteria causing the infection is found.

As a nephrologist, I do not do these procedures nor surgeries, but typically and importantly my focus is on the medical management of stones; their associated metabolic problems; the prevention of the formation of more stones in the future; and to give advice regarding the kidney function when they are blocking the urine flow acutely; or when they cause different degrees of kidney failure, and dialysis or similar therapies need to be considered.

How and why do urinary stones recur?

Unfortunately, many patients who develop a kidney stone can form more stones in the future; especially if the underlying medical or metabolic conditions associated with stone formation persist.

Suffering from chronic metabolic illnesses like metabolic syndrome or excess of weight (or others) is associated with stone formation. Similarly, having family predisposition to it (that is, running in the family) is an important factor. But some patients simply did not manage to implement the necessary preventive dietary and lifestyle modifications to sufficient degree so to prevent the formation of new stones; or they were actually not advised on how to prevent urinary stones.

In occasions, patients have multiple smaller stones and all of them cannot be removed during the procedures that I described before, and, as a consequence, one or some of them can grow with time; later giving problems to patients.

Urinary stones grow by continuous deposition of the salts that make them, sort of one layer after another; until the stone becomes of a significant size to be seen on an incidental scan or to give symptoms to patients like pain and blood in the urine.

In addition, if a urinary stone was fragmented surgically or through a procedure like lithotripsy, sometimes fragments of the original stone can remain after the extraction or fragmentation procedure, and bigger stones can grow on them with time.

How to prevent urinary stones?

For the prevention of the formation of new stones or the growth of existing ones is crucial to implement the necessary diet, fluid and lifestyle changes. This is because certain diets, eg rich in sodium (salt), low in potassium, low in calcium (contrary to what most people think), high in oxalate, low in citrate, high in uric acid, rich in sugars and simple carbohydrates, or high in animal proteins have been associated with higher risks of stone formation.

Similarly, drinking not enough water (being slightly dehydrated), a sedentary lifestyle, sugary carbonated drinks or taking some supplements like calcium supplements or vitamin C supplements can favour stone formation in predisposed patients.

In other words and the other way round, to prevent stone formation, a diet low in sodium (salt), sufficient in potassium, sufficient in calcium, low in oxalate, high in citrate, low in uric acid, low in sugars and simple carbohydrates, avoiding excess of animal proteins, and with plenty of fluids (not necessarily excess of fluids but at least 2 L/day) helps. In addition, moderation or avoidance (especially if not medically needed) of calcium and vitamin C supplements further helps.

A clinical dietitian would be the best person to advise on how to translate those recommendations to your daily meals. But I always give some tips to my patients, especially if not keen on seeing a dietitian. But I tell them to reconsider that: If there is an issue, it is better to sort it as effectively and targeted as possible.

It is also necessary to exclude and treat adequately any metabolic problems that patients might have like metabolic syndrome, gout, diabetes mellitus or even excess weight, which predispose them to stone formation. And by treating them, the risks of stone formation are minimised.

Some patients might have rarer diseases, which are associated with the stone formation and only after a thorough clinical assessment, they can be detected and some measures implemented.

Finally, some patients might have anatomical problems in the kidneys or the urinary tubes, and can develop frequent urine infections, which also predispose to stone formation; so detecting these infections opportunely and treating them can help, too.

As commented before, co-manage with a urologist is the way to provide more rounded advice and involving a dietitian does help.

What kind of tests do I need if I suspect that I may have a urinary stone?

First of all, having pain in the flanks and/or blood in the urine is suggestive of having a urinary stone, but seeing a doctor will be essential as indeed you might have it, but it could be something else.

A common suggestion from doctors, especially if a urinary stone has not been confirmed, is to do an ultrasound scan and an X-ray of the kidney and the urinary tract. They are affordable, non-invasive and provide minimal risk to patients. But if the suspicion of the stone is higher, or obvious, or it is already known to be there and its location or complications including obstruction want to be assessed, a CT scan or CT urogram is preferred; although this provides significantly more radiation than the others. There are other diagnostic alternatives and it is always better to consult a doctor.

Once the presence of urinary stones has been confirmed, I advise my patients to do some extra tests to exclude many of the metabolic conditions (mentioned in a previous section) associated with different types of urinary stones. Obviously, I also check what medications they are taking, take a detailed medical history, etc.

I suggest a chemical analysis of the urine in a 24h collection, including pH, calcium, uric acid, citrate, oxalate, sodium and potassium. The urine volume should be calculated, too.

A chemical analysis of the stone is pivotal if it is ever passed (or after being extracted), so we can identify more accurately what type of stones patients might be forming and target and personalise my medical, dietary and lifestyle advice more accurately to that type of stone.

In some conditions, we can prescribe preventive medications, for example, anti-gout medications for uric acid stone formers or some types of medications that can reduce the excretion of calcium in the urine when patients excrete high amounts of calcium in the urine like thiazides (reason for the urine chemical analysis; because it can be very helpful to decide on preventive measures); among others.

Overall, there are few types of stones with different associating causes and some distinct treatment or preventive measures, so our diagnostic strategy and treatment advice must be personalised.